#ARCTIC. #SIBERIA. THIS IS TAIMYR. Alexander Gorr was one of the first in the country to propose the use of local raw materials in the Far North for the production of food products on an industrial scale. He became a laureate of the USSR Council of Ministers Prize for the Norilsk meat processing plant launch.

From Alexander Gorr’s memoirs:

“Approximately in the mid-1960s, after the Talnah construction began, the Big Norilsk population grew rapidly. There was the need to increase the production of local food enterprises. After all, until Norilsk mastered the production of its own confectionery and bakery products, cookies, waffles, gingerbread, the shelf life of which was three months, had to be delivered by plane.

But it’s easy to say, but not easy to do… How to import additional volumes of raw materials to Norilsk for the production of “their own” gingerbread, if aviation delivered 20 thousand tons of apples, citrus fruits, fresh chicken eggs from state farms? There was not enough cargo aviation even for planned cargoes, not to mention overplanned ones.

The second problem is that air transportation is more expensive than river and sea transportation, the delivery of raw materials by air sharply increased the costs. Now, in a market economy, an entrepreneur includes all expenses, including air delivery, in the price of the goods and ultimately reimburses the costs at the expense of the buyer. But in those days, retail prices were approved by the center, and a kilogram of cookies had to be sold at a single price, regardless of whether you brought it by river, by air, or made on the spot.

Together with the combine’s management and the city council’s executive committee, we, the trade department employees and food workers, have been looking for a way out of this situation for a long time. We came to the conclusion that it is necessary to increase the food enterprises capacity and the products output – primarily with a short expiry period. Therefore, every year the increase of the Norilsk food industry output was 10–11 percent (while the main production grew by about a percent a year).

Much had to be rebuilt on the go. The factories’ material and technical base was completely unsuitable for such growth rates. Sausage production was organized in the premises that used to house forced labor camp barracks. Accordingly, the oldest equipment worked there. Every year, large sums of money were spent on major repairs, and, if possible, unusable equipment was replaced. I remember how willingly the directors of other enterprises met our requests. For example, the CHPP director, Stanislav Korsak, personally prepared the drawings and participated in the installation of special boilers for cooking sausages; metallurgists suggested how to make drying ovens and so on.

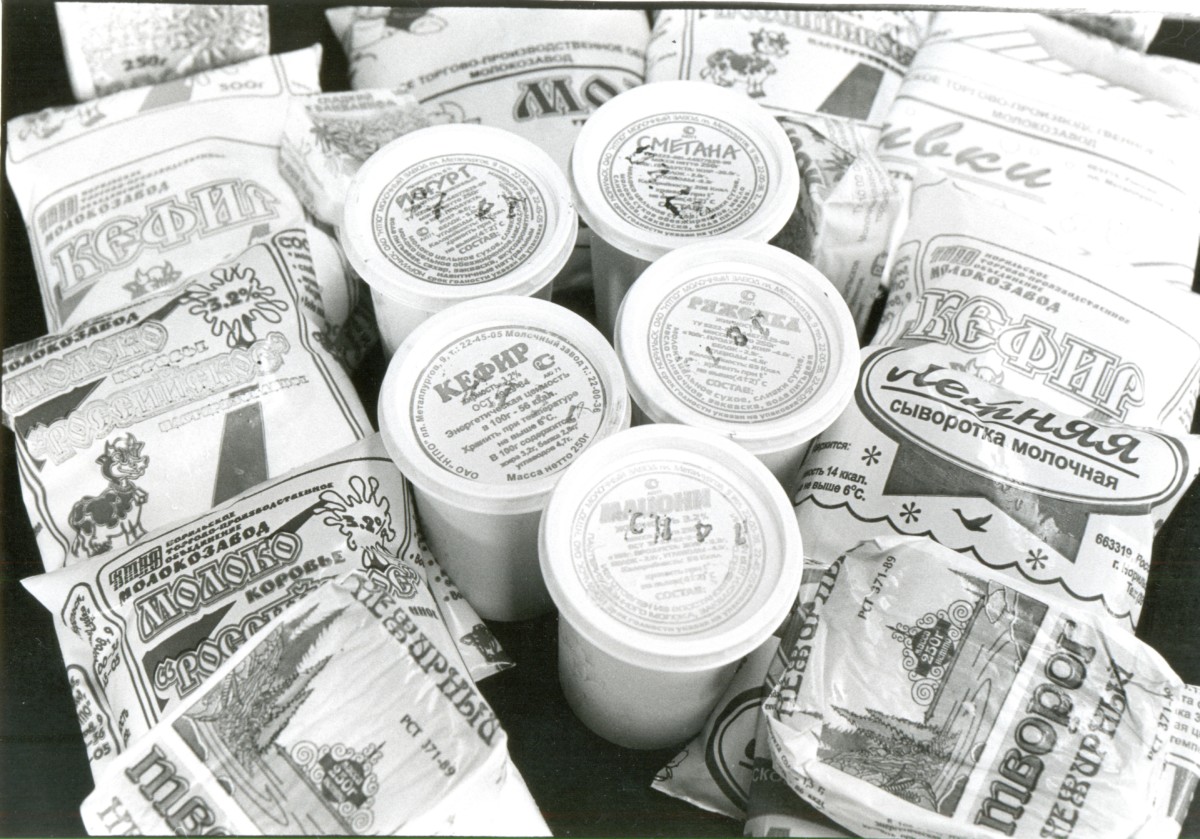

The dairy was located in the village of Semerka. It was also an old enterprise, suffering from overcrowding, lack of production capacity. Although even there we were able to install several machines for filling milk into tetra packs. Norilsk people still remember that Norilsk milk in pyramidal packages! Thanks to this packaging, we finally got rid of glass containers that were laborious for the plant and inconvenient for the buyer. Indeed, before the advent of tetrapacks, every working day at the dairy began with manual dismantling and washing dozens of technological pipelines (more correctly, milk pipelines) in a special solution in order to maintain the required level of sterility and sanitary safety…

By the beginning of the 1990s, food production by all food factories amounted to over 50 million rubles a year. Quantitatively, it looked like this: bakery products – up to 60 tons, dairy products – up to 120 tons, meat products – up to 30 tons daily. Every year Norilsk residents drank 12 million liters of fruit juices and 400 thousand liters of beer. Over 1 500 people were employed in the food industry”.

In the History Spot’s previous publication we told that at the end of 1956 Kayerkan officially became known as a workers’ settlement.

Follow us on Telegram, VKontakte.

Text: Svetlana Ferapontova, Photo: Nornickel Polar Branch archive