The memories of Vitold Nepokoichitsky about the urban planning experience of the first designers were written down in 12 notebooks. For the first time, manuscripts were taken from the museum funds for the exposition dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the combine in 1995. After 10 years, the memoirs made a separate exhibition.

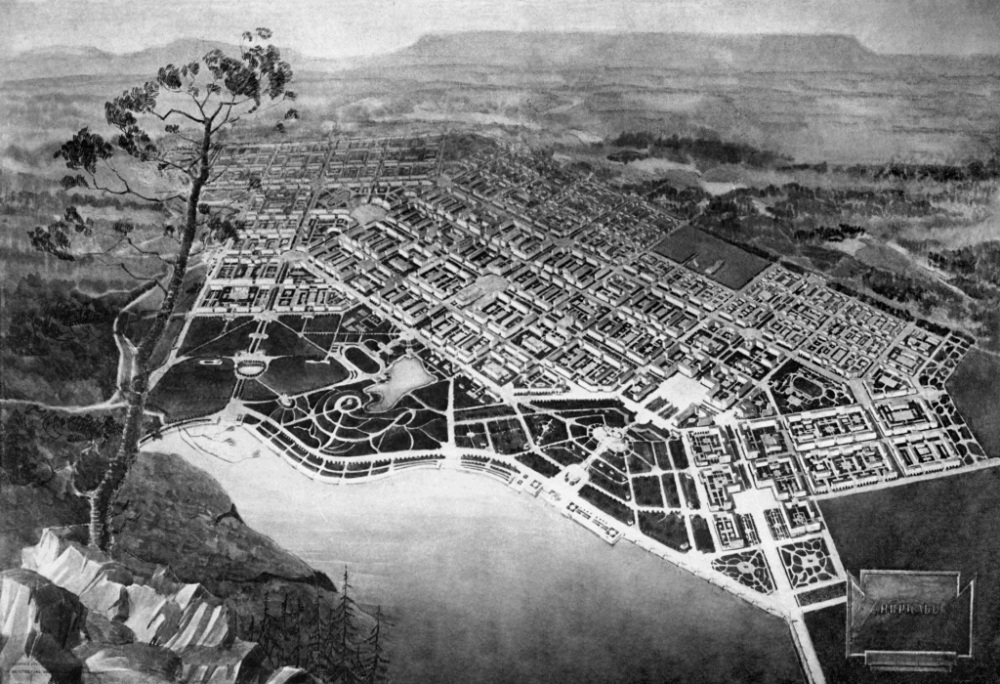

On the occasion of the 105th anniversary of the former city’s project’s chief architect, a Norilsk resident from 1939 to 1973, the museum organized the exhibition named Green Notebooks. This year, on the occasion of the 110th anniversary of Nepokoichitsky, the exposition consists of the architect’s photographs and watercolors, made in Norilsk in the 1940s and 1950s. Plans and sketches illustrating the stages of designing and constructing of the city on the 69th parallel were exhibited more than once in different formats.

Vitold Nepokoichitsky was a multifaceted personality. The architect’s legacy is not limited to the buildings and structures erected according to his designs on the permafrost. Even during Vitold Stanislavovich’s lifetime, in the memorial complex of Zavenyagin’s house on the Zero Point, Nepokoichitsky’s “museum room” was allocated, where projects, documents, photographs of the architect were presented. The hero himself did not fly to the opening of the complex, but his memories from the “green notebooks” helped to recreate Zavenyagin’s office and the house itself, and the materials donated to the museum filled his personal room. Nowadays, few people remember those expositions, since the house stayed there for less than five years.

The value of the Nepokoichitsky’s manuscripts from the museum collection lies in the fact that from them you can learn firsthand how it all began. Obtain the author’s characteristics of the first designers, about whom there is so little information. Of course, the story is primarily autobiographical.

It begins in Leningrad, from where a married couple of architects started their way to Leningrad – Moscow – Krasnoyarsk – Igarka – Norilsk in the summer of 1939. In Krasnoyarsk, the author and his wife, Lydia Minenko, liked the Stolby reserve most of all, which they went to with a group of specialists traveling to Norilsk. And then they got on a plane, since there was no room for the future Norilsk residents on the steamer. A fascinating description of the flight takes more than one page: “And suddenly the broken outlines of the mountain range turned blue. I stared straight ahead… Most of all I was afraid that the plane would turn off somewhere and leave the slowly approaching mountain range… Will I never see this pristine beauty?! – I thought with involuntary sadness. Could I assume that I would spend more than 30 years of my life there?”

In the same detailed way, in good language and with good humor, Nepokoichitsky described his first acquaintance with the camp village and the construction manager Avraamy Zavenyagin. He recalled his first home on Zavodskaya Street and, most importantly, work. According to Anatoly Lvov’s (a well-known historian, journalist, the author of many books about Norilsk) definition, work was the third deity to which the architect Nepokoichitsky prayed all his life. As deities, he also worshiped two women: his mother and wife.

The memoirs end with Nepokoichitsky’s last meeting with Zavenyagin. In 1949, the almighty Deputy People’s Commissar helped the “indigenous” Norilsk resident get a voucher for treatment in a sanatorium. The architect returned to Norilsk from the Crimea without any traces of his illness. Then he often visited Moscow on business, but did not see Zavenyagin again.

The honorary citizen of the city, who believed that Octyabrskaya, Gvardeyskaya and Komsomolskaya squares, Sevastopolskaya and 50 years of October streets, which determined the appearance of Norilsk, arose as a result of their creative collaboration with Lydia Minenko, also calls Zavenyagin his co-author. They chose a site for construction together and defended the general plan of the city.

In his memoirs, Nepokoichitsky wrote about many of his colleagues, including the Norillag prisoners Mickael Mazmanyan and Gevork Kochar, who took part in drawing up the general plan of Norilsk. Perhaps, if the memoirs were written later, during the years of perestroika and glasnost, there would have been more details about the Norilsk period by famous architects.

Before his death (August 26, 1987), Vitold Nepokoichitsky began “recollections, starting from scratch, that is, from appearing in the sublunary world”. He managed to write 19 notebooks with his perfect handwriting. And they are also kept in the Norilsk Museum.

Read about other unique items from local museums in our Artefacts section.

Text: Valentina Vachaeva, Photo: Norilsk Museum and Severok1979.livejournal.com