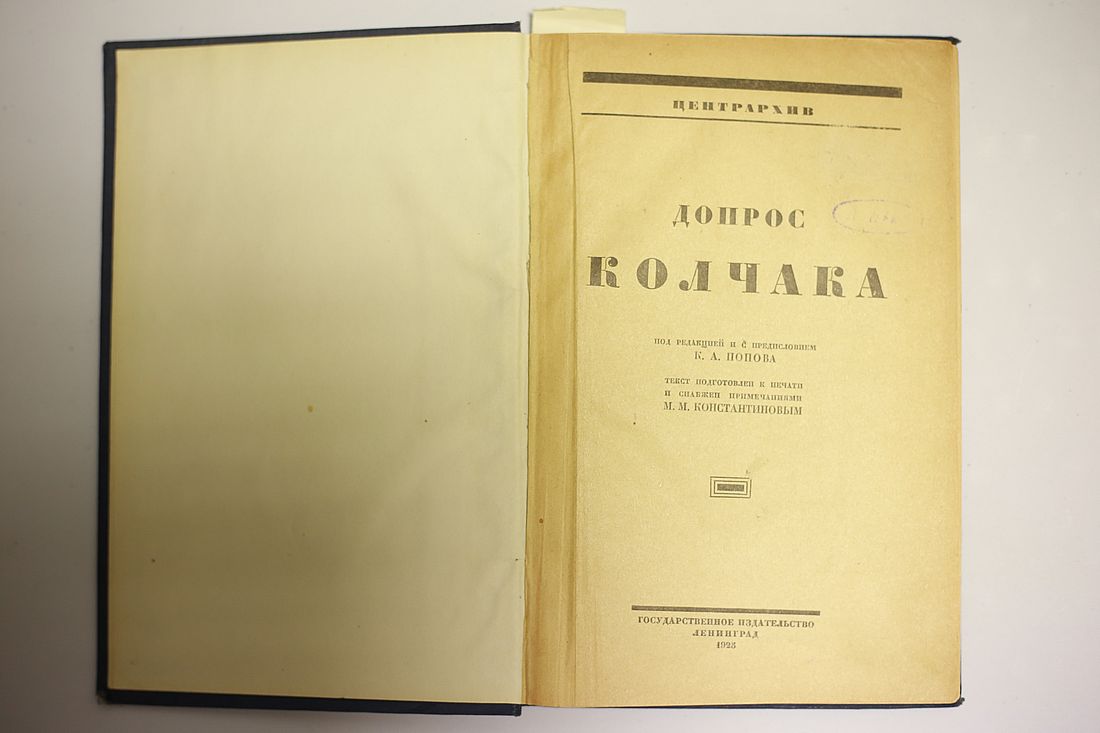

A verbatim record of the Extraordinary Investigative Commission meetings on the case of the Russian government in Omsk Supreme Ruler, as Kolchak called himself, was published five years after his execution, in 1925.

The circulation of the edition is only 10 thousand copies. One copy was acquired by the museum from the local collector Valentin Komarnitsky.

For a long time, practically all his life, Nikolay Urvantsev, the scientific leader of the first expedition to Norilsk, directed by the Siberian Geological Committee created under Kolchak’s rule, was called kolchakian. Anonymous letters (they are in the museum) were addressed to a variety of authorities. There were messages, for example, to the Central Television. In one of them, dated May 5, 1970, the future honorary citizen of Norilsk was accused of sympathizing with Kolchak on the basis that Urvantsev named the mountain after his teacher, Professor of the Tomsk Institute of Technology Pavel Gudkov, who emigrated to the United States. If all the blinkered took an effort to read Kolchak’s Questioning, and the book, oddly enough, was not banned, then perhaps it would have helped most of them at least rethink their attitude towards the admiral.

The first reliable information about the role of Alexander Kolchak in the history of Russia dates back to the perestroika in the 1980s. If until that time he was known in the Land of the Soviets as a White Guard, self-styled Supreme ruler, hangman, then at the end of the 20th century they started talking about Kolchak as a talented naval officer, explorer, discoverer of the northern lands. Memorial plaques and monuments were opened in Russia, and the question of his rehabilitation was considered. There were films, theatrical performances dedicated to the admiral. The media flooded publications about how Kolchak and baron Toll were looking for Sannikov Land, his participation in the scientific expedition to explore the Northern Sea Route on the Vaigach icebreaker. But even more filmed, staged and wrote about the admiral’s love triangle.

During the interrogation, Kolchak answered not only questions about his participation in expeditions, the Russo-Japanese War, World War I and the struggle against Bolshevism. The members of the Extraordinary Commission also asked about the admiral’s personal life. At the very first meeting, the person under investigation was ordered to clarify what relation Ms. Timireva, who was also arrested, had to do with him. To help his beloved woman, Kolchak asked to record Anna Timireva not as a common-law wife, but as a good friend who worked in Omsk in a linen workshop and who wanted to share his fate.

From January 21 to February 6, 1920, the 46-year-old admiral was telling the story of his entire life in great detail, without reservations. The speech of ‘an ardent enemy of the Soviet regime’ was filled with the words ‘duty’, ‘honor’, ‘dignity’, ‘Motherland’. There was no aggression in his answers, but there was no hope in them to be understood either.

The interest in the legendary personality has not dried up even 100 years after his death. The Interrogation of Kolchak book was exhibited in the museum only once, at the exhibition of new acquisitions in 1991, but it helped the famous playwright Mikhail Durnenkov in creating the Kolchak Polar play. The main director of the Norilsk Polar theater Anna Babanova is already finishing the work on the play. The premiere is scheduled for October 17-18.

Text: Valentina Vachaeva, Photo: Norilsk Museum and open sources